Why are we sometimes inclined to believe in the improbable against all odds? A study conducted at the École Normale Supérieure and Hôpital Sainte-Anne by a team of neuroscientists and psychiatrists from Inserm, the University of Paris and the Paris Brain Institute, points to a specific synaptic receptor. Its blockage induces premature and aberrant decisions, as well as symptoms resembling those reported in the early stages of psychosis. The results have just been published in Nature Communications.

When the world around us becomes unpredictable and uncertain, we become more likely to believe the improbable – such as conspiracy theories during a pandemic. This type of reaction to uncertainty is seen most acutely during the early stages of psychosis: a general sense of strangeness precedes the emergence of delusional beliefs. These early stages of psychosis are difficult to study, as patients only access care when delusional beliefs are already established.

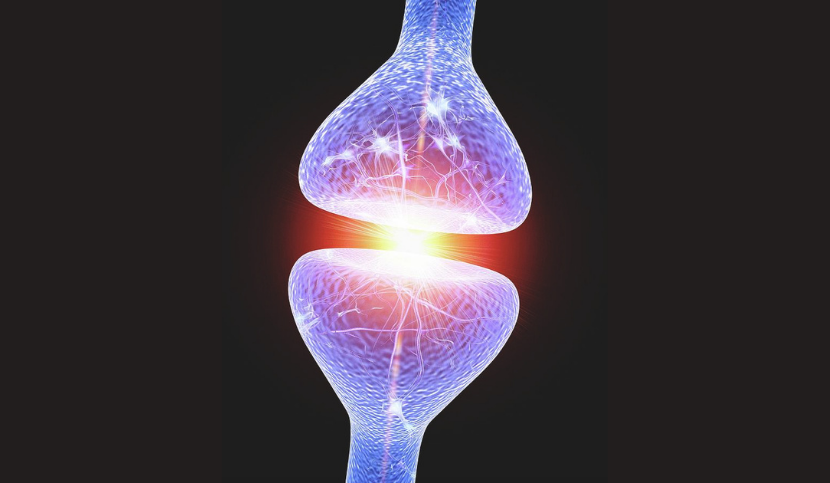

The team, led by Valentin Wyart, Inserm research director at the Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience Laboratory (Inserm/ENS-PSL) and Professor Raphaël Gaillard of the University of Paris at Hôpital Sainte-Anne-GHU Paris, studied the role of a specific synaptic receptor called NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) in the emergence of these aberrant beliefs. In the brain, synaptic receptors regulate communication at synapses, the areas of contact between neurons. The researchers did not become interested in this receptor by chance. Indeed, encephalitis caused by an autoimmune reaction against the NMDA receptor is known to give rise to psychotic symptoms.

To understand whether an abnormality of this receptor favours the emergence of aberrant beliefs, the team asked a group of healthy volunteers to make decisions based on uncertain visual information while being administered a very low dose of ketamine, a molecule that temporarily blocks the NMDA receptor. By comparing the effects of ketamine with those of a placebo on the behaviour and brain activity of the volunteers tested, the researchers were able to determine the effect of ketamine on the behaviour of the volunteers.

In comparing the effects of ketamine with those of a placebo on the behaviour and brain activity of the volunteers tested, the researchers observed that the administration of ketamine produced not only a heightened sense of uncertainty, but also premature decisions.

“A blockade of the NMDA receptor destabilises decision-making, favouring information that confirms our opinions to the detriment of information that invalidates them,” explains Valentin Wyart. “It is this reasoning bias that produces premature and often erroneous decisions.”

It is this type of bias that is particularly blamed on social networks, which offer users a selection of information based on their opinions.

The team went further by showing that this reasoning bias compensates for the high feeling of uncertainty experienced under ketamine.

“This result suggests that the premature decisions we observe are not the consequence of overconfidence,” continues Valentin Wyart. “On the contrary, these decisions seem to be the result of high uncertainty, and provoke the emergence of ideas that are highly improbable, and which are self-reinforcing without being invalidated by external information”

These results open up new avenues for the management of patients with psychosis.

“Our treatments act on the delusions, but do little to influence what causes them,” explains Raphaël Gaillard. “Clinical trials should therefore be carried out to determine how to increase patients’ tolerance of uncertainty in the early stages of psychosis.”